Will an MRI Make Back Pain Better or Worse?

by: Robin Dufour- Posted on May 4, 2020

It depends. In fact only 5% of people with back pain need an MRI or CT to investigate a serious problem. Flip that, and we know 95% of people with back pain don’t benefit from images. So what’s the harm in checking? You may be surprised by the answer.

We’ve all said it, “a picture is worth a thousand words” and in most cases, I agree. Our minds can conjure up entire novels from one photo. Art can inspire generations to think and feel and do amazing things. Shouldn’t a high tech picture of our spine speak volumes about back pain? Time and again, science and experience tell us the answer is no.

It makes sense that if we have back pain and the technology is available, we want to see what’s going on inside. The temptation is strong for many practitioners and patients alike. Let’s get that picture to tell the story, have the doctor fix it and move on to bigger and better things.

This is where countless people have been lead down a long, rough road.

The vast majority of back pain is musculoskeletal — meaning an over-use or under-use of the muscle, connective tissue, and cartilage. It is movement related pain. This is something the literature has been clear on for years. Unfortunately, it’s still being treated like a disease that requires highly advanced medicine to detect and fix. Conservative management even sounds boring.

The solutions with the best results and least risk are low-tech and take some effort. It’s appealing to think pain can be fixed my medicine. As a result, common sense solutions don’t get much attention in modern medicine, advertising campaigns, or the media. As a Physical Therapist of 20+ years and ever curious person, I’m in the camp that believes simplicity is the key. Several years ago I did a talk for a group of practitioners from around the world titled, The Power of Know. As often happens, a Steve Jobs quote was central to the main idea:

Simple can be harder than complex: You have to work hard to get your thinking clean to make it simple. But it’s worth it in the end because once you get there, you can move mountains.

If you feel good, you can also climb mountains. Outcomes are what matter. If you feel good, you can golf, walk, run, pick up your kids and grandkids — you can live.

Take Linda for example. She’s a very young 70 year old artist with a sharp wit and kind heart. Her stories are nothing short of fantastic. Linda had low back surgery several years ago and came to see me in hope of some relief before her next one. Her surgeon said another fixation was the only way to stop the pain that has been gripping her back and traveling down her left leg for months. A second surgeon recommended physical therapy, “when that doesn’t work, we can do the surgery.” Perhaps not the best endorsement for the conservative approach.

She brought her MRI and CT for me to look at as we discussed her situation. I know Linda, I’ve been to her home for dinner. She asks about my girls and tells me I’m doing a good job with them. This is the kind of person Linda is. She’s in pain, can’t enjoy what she loves doing, yet still asks about my family.

I take a look at the MRI, though I already know what it’s going to say. The CT, apparently taken on the same day — not sure why both were done, perhaps because her insurance would cover it and both machines were right there in the office— gives the same information. There is a surgical fusion and decompression at L4/L5, now the joint above [L3/L4] is being over stressed. It shows an S curve in her upper back (scoliosis), which is evident by simply looking at her posture. The disc in the space between L3/L4 is bulging from the pressure and encroaching on the nerve that branches from that level. This is happening because the joint below [L4/L5] can’t move anymore, and the curve in her upper back is creating stress from above.

Many surgeons will mention in passing that in a few years you’ll probably be back for another fusion— ‘no worries, we’ll fix that too.’ I am not implying that all surgeons are walking around twirling their evil mustaches. There are plenty of docs openly speaking out about the low success rate of spinal fusion, which is 25–35%. Placebo effect is arguably somewhere between 25–50%. I’m not a math genius, but those aren’t good odds for the risk of surgery, the prevalent complications, and the high chance of needing another one in a few years.

In 1993 Dr. Gary Franklin published a paper showing that the return-to-work rate in the state of Washington after a spinal fusion for back pain was 15 percent. In a two-year followup, the return-to-work rate was 22 percent. Dr David Hansom, an orthopedic spine surgeon says those results got his attention.

“And then I looked at my own results. I looked at that data and I just stopped, because I realized that the fusions for back pain were not doing well.

Then about the same time a lot of my patients that had had fusions started breaking down above and below their fusions and a lot of patients became referred to me for breakdown above and below their fusions. And those are real problems. Those don’t do well without surgery.”

We can do better. We must do better.

After hearing Linda’s story, I asked if we could take a look at how she’s moving. “Has anyone watched you move?”

“No.”

“Did anyone show you what you can do to open up that space where the disc is under all that pressure?

“No…can you really do that?”

You may think this is unusual. To be told surgery is the only answer even though none of the experts in Linda’s care had watched her move. Even worse, to be given no strategies to relieve the pressure causing the pain.

This is the norm and it’s a shame.

No Disc is an Island

Discs don’t bulge because they feel like it, or they are inherently faulty. Discs are firmly attached to the vertebrae and are constructed brilliantly to absorb shock. They are part of the human ecosystem.

They don’t slip out of place. They bulge when ‘abnormal’ forces are exerted on them over time. If they don’t find a nerve to hit, the bulge doesn’t cause a problem. The factors contributing to stress are the problem and they can be addressed. The stress can be physical, social or emotional — most likely a combination of the three. Think ecosystem, not island.

Even if a disc is painfully bulging into a nerve, it can be resolved without surgery. In addition, “the risk of subsequent catastrophic worsening without surgery is minimal.” The New England Journal of Medicine published a study that definitively shows a protruding disc can resolve with the right conservative management (there’s that boring phrase again, let’s call it changing the ecosystem instead).

Often when surgery is done to fuse the vertebrae, nothing is done about the surrounding ecosystem that caused the problem in the first place. It’s like putting an old beach house on stilts even though the water is still eroding the beach and the next hurricane is only a matter of time.

After doing a movement assessment (3DMAPS) with Linda, it was clear where to begin. Her scoliosis isn’t fixed — meaning it changes with movement. Her hip motion is tight in some key areas, which the low back doesn’t like. We needed to teach her three moves to relieve the pressure. It’s not rocket science, it’s functional biomechanics. Unfortunately, there are very few practitioners who understand how to apply it.

I showed Linda the three moves, we recorded them on the mobile app we use to communicate with clients so they’d be on her phone. We did some soft tissue work through her hips, legs and upper back on the table. Linda left feeling confident about what she could do on her own and with us in the studio. That’s always the mark of a good first session, you should leave feeling more confident.

Another observation worth noting here is what happens to the paraspinal muscles after lumbar fixation. Along the incision, there is almost always a 2″ to 3″ long divot where the paraspinal muscles have denervated and atrophied. I see this over and over when working with people a year or more after surgery.

Surgeons don’t seem to be concerned with this loss of nerve connection and resulting muscle atrophy surrounding the surgical site. I’ve never had a client who was aware of it before we discussed it. The literature on paraspinal muscle atrophy following lumbar surgery is minimal. We definitely know it happens a lot. One study says it probably has detrimental effect. Common sense would say that if the muscles directly attached to the bones don’t work anymore, then that’s not good. Sometimes you don’t need a study.

Another finding on Linda’s MRI was anterolisthesis of L3 on L4. That means an anterior or forward ‘list’ of one vertebrae on another. A reasonable hypothesis would be, if the paraspinal muscles are damaged after surgery, there is a greater chance of instability in the surrounding joints. Add onto that, therapy or exercise that doesn’t address the asymmetries (ecosystem) that caused the problem in the first place and we’ve got another storm on the way.

On her second visit Linda came in laughing and shaking her head. She’d not had any of the spasms or the aching pain down her leg that had been with her for months. As of this writing, it’s been 6 weeks since Linda’s first session and she’s doing very well. By that I mean she’s playing 9 holes of golf when she wants to and has had a chance to investigate her options in relative comfort.

“I’ve had PT so many times that didn’t do any good, the surgeon said I need surgery to fix it, and now I’ve had almost two months without that awful pain.”

We are not out of the woods yet. There are longstanding patterns in her body that will take over if she doesn’t continue to create new pathways of movement. Soft tissue work is also helpful in getting good circulation and clearing painful inflammation.

Some would call this pain management. I don’t like the negative conation of that term. She is rebalancing and redistributing the forces going through the disc at L3/L4, making is less likely for the nerve to be hit, and that is taking the pain away. She’s changing the ecosystem. It’s not rocket science, it’s functional biomechanics mixed with the confidence of going from a state of vulnerability to empowerment.

She has options and actionable information. She’s in significantly less pain, and therefore in a better position to make informed decisions. In the end, we all make our own choices and the more we know, the better.

I’ve given her a copy of Cathryn Jakobson Ramin’s book, Crooked: Outwitting the Back Pain Industry and Getting on the Road to Recovery. Ramin is an investigative journalist who’s experience with back pain led her down the rabbit hole. The five page bibliography alone is better than any Google search. We bought ten copies to loan out and pass on.

Back pain is not the unsolvable enigma it’s been made out to be. I learned how to interpret and apply principles of physical, biological and behavioral science at the Gray Institute after 15 years of practicing physical therapy. I’ve had the great opportunity to teach for them since 2013. The more practitioners that take the time to understand the why behind the what the better.

Dr. Gary Gray and Dr. David Tiberio of the Gray Institute are the pioneers of Chain Reaction Biomechanics. For over 30 years they’ve been humbly seeking to better understand the human ecosystem in the field of Applied Functional Science (AFS).

We’ve been trying to fix things that aren’t broken

There are normal changes that take place inside the body over time. These normal changes show up on MRI, CT and X-ray to take the blame for crimes they didn’t commit.

Research and peer review articles have been clear for years. Do an MRI or CT when there are neurologic signs and symptoms — like loss of bowel and bladder function. Otherwise, you may be doing more harm than good.

Modern medicine runs on a high tech, diagnose and treat mentality. Atul Gawande’s 2015 New Yorker article, Overkill is a call to common sense action.

The phenomenon of over-testing, [which] is a by-product of all the new technologies we have for peering into the human body. It has been hard for patients and doctors to recognize that tests and scans can be harmful. Why not take a look and see if anything is abnormal? People are discovering why not. The United States is a country of 300 million people who annually undergo around 15 million nuclear medicine scans, 100 million CT and MRI scans, and almost 10 billion laboratory tests. Often, these are fishing expeditions, and since no one is perfectly normal you tend to find a lot of fish.

What’s the harm in ordering an MRI or CT to diagnose back pain? The science (and the outcomes) are consistent in showing one thing – in the absence of neurologic impairment or history of cancer, the scans add nothing but cost. Real people are paying the financial, social, and emotional price.

The general public has no idea that the literature very rarely indicates the need for MRI or CT to diagnose and treat low back pain. So many people get them, that everyone knows someone who’s had an MRI for musculoskeletal pain. It’s engrained in our conversations and in our culture. The results of these costly tests leave countless people no closer to an answer than when they started. What they do is wrongfully leave you with a sense that your back is damaged and vulnerable.

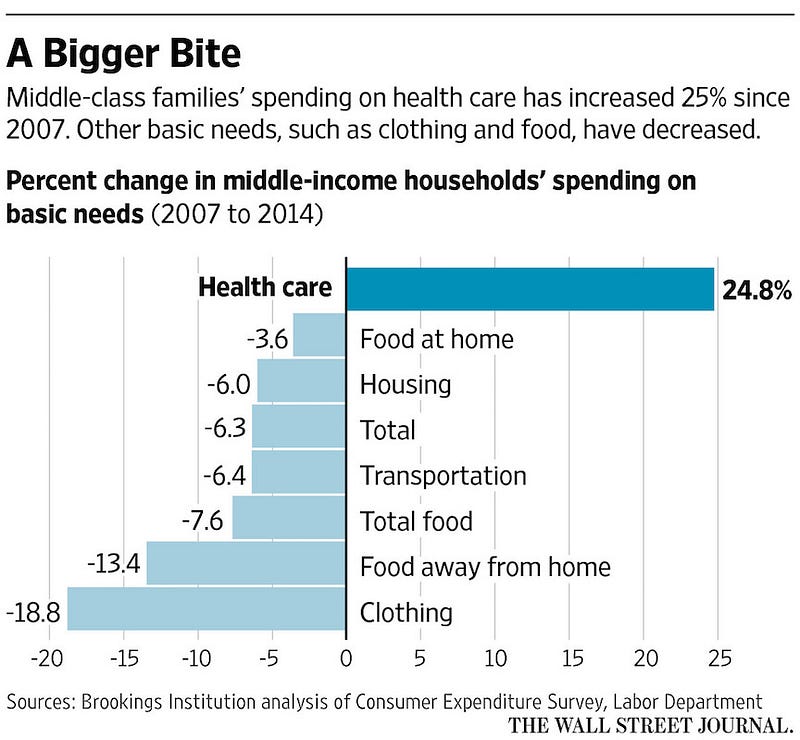

The unneeded scans (average cost is $2611) often lead to an avalanche of treatments with low to no value. We are spending upwards of $3.3 trillion a year on health care. Economists would blame (surprise!) economics. A reasonable economic explanation for the excess of low value care is the combination of fee for service and third party payment. Providers are paid more for doing more, while insurance foots most of the bill.

In reality, the patient and their employer are paying with the annual rise of premiums and deductibles to cover the previous year. Premiums have doubled every eight years for the past four decades. The rising cost for the fishing expeditions Gawande refers to is completely out of proportion to other basic needs. If we were getting better results the cost wouldn’t be under such scrutiny.

We can do better

While the economists have a valid point, it’s only one piece of the puzzle. According to the Archives of Internal Medicine, roughly half of the physicians polled said their patients received too much medical care. Too much doesn’t just imply wasteful care, but also harmful care. Many doctors point to ‘defensive medicine’, a phenomenon brought about by the fear of being sued or wracked with guilt if they miss something.

I think of our third party payor system as an open bar problem. An open bar feels free. On someone else’s dime, it’s top shelf all night. Maybe two drinks at a time to avoid waiting in line. At the end of the night it’s spills, and empty tables cluttered with 1/2 full drinks.

Imagine ‘free’ drinks and the bartender being paid more for every drink served. Yikes! That’s pretty close to fee for service care in a big medical system with a third party footing the bill. While economic incentives matter, there is a fundamental flaw to in trying to blame the entire problem on fee for service and third-party payments.

None of that would matter if the general public didn’t believe in the value of the service. Not only do we believe in it, since we pay the high premiums, we deserve it. Of course we deserve to be cared for compassionately and competently. The question is, when do we really need medical care and when do we simply need to change a few behaviors? In other words, when is it medical and when is it functional?

Dr. H. Gilbert Welch, an academic physician and professor at Dartmouth Medical School, is a heavyweight in the fight to bring awareness to the dangers of over-diagnosis and excessive medical testing.

“The general public harbors assumptions about medical care that encourage overuse. Assumptions like it’s always better to fix the problem, sooner (or newer) is always better, or it never hurts to get more information.”

When we start to talk about saving money and thinking twice about getting diagnostic tests, it gets…uncomfortable. Emotions run high. It’s not about saving money, denying care, and putting people at risk. Think less medicine and more health. It’s about common sense, informed decisions, and awareness of actionable options.

When it comes to our health and that of our kids, parents and loved one’s, it’s the outcomes that matter. More treatment is not always better. The outcomes of high tech testing and procedures — particularly with musculoskeletal issues — mean more medicine, not necessarily better health.

It goes without saying, we want the best care for ourselves and our loved one’s. The problem is, it’s increasingly difficult to filter out the noise and confidently know what’s best. Dr Hansen’s experience as a surgeon who has chosen to do less surgery is particularly interesting:

“So it’s actually fairly unpleasant to tell a patient who is demanding surgery — that you can’t do surgery, number one. Second of all, doctors do get paid well for doing surgery. We don’t get paid well for not doing surgery. So the patient’s demanding surgery. The hospital system is demanding production, which means more procedures, but also the patient’s themselves would rather have something done to them than to do something for themselves, like do solid rehab, etc.”

Back pain is a $100 billion industry in need of disruption

The source of the majority of back pain is musculoskeletal in nature and not detectable on an MRI or CT. We find the cause within your story and in the way you move (look for a practitioner certified in 3DMAPS). Your doctor or therapist should be a skilled and attentive interviewer. Questions like, “how can I help you?”, “what’s been going on?”, and “tell me more about that…” can reveal more than any diagnostic test.

Daniel Cherkin, a back pain specialist at the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute says, “[Back pain is] not the only thing that’s been overmedicalized, but it’s probably the poster child for how things can go wrong in terms of patient outcomes and cost to society.”

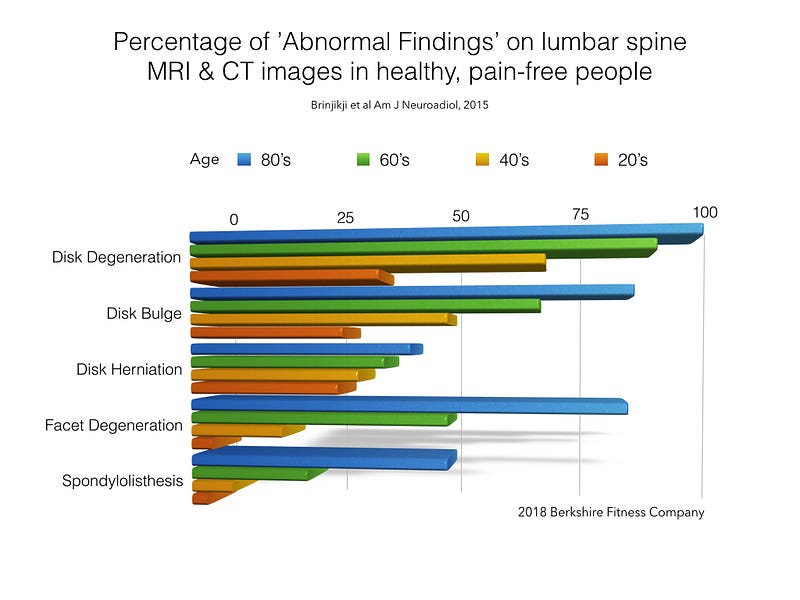

Discs degenerate. Sometimes they bulge. At times they even protrude. These so-called abnormalities get a bad rap. They exist in as many people in pain as not. When they pop up in a high tech fishing expedition — often after years of being there, doing no harm — it’s assumed they must be the cause.

It’s no surprise that our skin looks different at 20 than it does at 65. We see our skin with every glance in the mirror. It’s in our face everyday, which makes it easier to accept as a ‘normal’ sign of a life being lived. We can’t see what’s under the skin, so we rely on the experts to analyze the pictures and let us know what’s normal and what’s not.

Discerning what is an unavoidable process of aging vs. a disease process should be the headline of every image report. For example, Degenerative Disc ‘Disease’ is a misnomer. Disc degeneration is a normal process that begins in our 20’s. It is not a disease and it does not cause pain. It’s old school science for a practitioner to think a degenerated disc causes pain.

Dr. Gawande says, “our ever more sensitive technologies turn up more and more abnormalities — cancers, clogged arteries, damaged-looking knees and backs — that aren’t actually causing problems and never will.’

These so called abnormalities exist in significant numbers of healthy, pain-free people of all ages. They are there whether we have pain or not. The graph above shows results from a 2015 Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations. Literature reviews are great because they look at multiple studies to find common ground. This one looked at thirty-three articles reporting imaging findings for 3110 pain-free people.

We can see that 37% of pain-free people in their 20’s have disc degeneration. It’s natural. 50% of pain free people in their 40’s have a disc bulge, and 36% of people in their 50’s have a disc herniation. It’s worth saying again, these are people without any pain.

If a herniation encroaches into a nerve space, there will be pain along the path of that nerve. The good news is, if you are working with someone who understands how the body moves, it’s likely they can help you open that space and relieve the pressure naturally. The same approach works for stenosis — the narrowing of the spaces that house spinal nerves.

Harvard Medical School agrees that Physical Therapy is just as good as surgery and less risky. Surgery should be avoided, especially when the success rates hover around 30% and the risks are high. A recent Johns Hopkins study found that medical errors are now the 3rd leading cause of death in the U.S. Too much medicine, not enough health.

It’s clear in the literature that images for non-neurologic back pain lead to over-diagnosis. This occurs when so called abnormalities are diagnosed as the source of the pain. We know degenerative discs are not painful. Remember, a disc is not an island, it’s part of the human ecosystem.

We know a large percentage of the population is walking about with bulges and herniations that do no harm. We know that even if the disc has protruded into a nerve it can recede naturally if the forces causing it to disperse are redistributed. We know enough about human movement to teach anyone how to do it.

As Steve Jobs said, it takes effort to get your thinking clean, but once you do it’s worth it. Not only can we move mountains, we can climb them if we want to.

Do no harm

A functional dynamic systems approach to musculoskeletal pain and discomfort is essential. The cause depends on our unique circumstances and experiences. The answers lie in the details of our stories and what we are willing to see and change— not in a single, static snapshot of our insides.

So when is an image the right thing to do?

There are a few red flags that you and your doctor must attend to. Loss of bowel and bladder function, loss of muscle control, and loss of feeling. Depending on your history and presentation, there are other valid reasons for testing. In Linda’s case, since she already had a spinal fusion years ago, it was probably a good idea to get an MRI based on her symptoms. We know after spinal fusion, the chance of instability above and below exists. I would still argue for the right conservative approach before jumping back into surgery.

In the same vein, as a PT, I’m fully aware that all physical therapy is not created equal. Use your judgement and don’t be afraid to ask why your PT chose a particular exercise or strategy. They should be able to give clear and concise explanations. Also be wary of clinics that do too many modalities (heat, ultrasound, electric stimulation) and not enough skilled investigation.

Good health care is like any good relationship. You should always be able to have an open and honest discussion with your doctor or therapist. The more a practitioner knows about you the better. The more interest they show in you, the better. If you feel like you aren’t heard, find someone who listens. Technology has made it possible for us to build relationships across the miles — both personally and professionally. We use encrypted technology for secure online consultations.

If the red flags aren’t flying, there are three questions to ask any practitioner who recommends an MRI, CT or X-ray for back pain:

Will it tell you something you don’t know already based on my history and current situation?

Does the research support the need for imaging to inform my treatment?

Will this test improve the quality of my life?

If the answer is no, or the practitioner struggles to find a clear answer, you’d do well to get a second opinion.

Book a Session

Book a Session